Managing performance of intangible policy objectives

Performance management of public sector programs

When governments develop new policies and implement programs to deliver on those policies, there is much to consider in terms of achieving good governance. There is often considerable effort put into delivery planning, compliance and even risk management but typically managing performance of a program in terms of delivering on the policy objectives is given scant attention.

All too often monitoring and reporting of such things as key performance indicators (KPIs) are not in place and there is little done in terms of feedback and continuous improvement.

This is not surprising. Many policy interventions and programs are difficult to measure in terms of their impact on, for example, the health of society, social cohesion, industry growth or change in community behaviour to name just a few.

However, with careful planning and a practical approach success of a government program and policy can be monitored and therefore managed.

Where government agencies are planning a new program, decisions need to be made about such matters as how it should be delivered and who should deliver it, as well as how it should be governed, including decision-making structures and roles of stakeholders. Where new legislation is involved, governments are also expected to consult widely and assess the potential positive as well as negative impacts often via a regulatory impact statement. Planning for the implementation of the program then commences. Generally agencies and bureaucrats understand issues such as project plans, resourcing, agreements that need to be struck and the like, even if these are not always done well.

A model for good governance

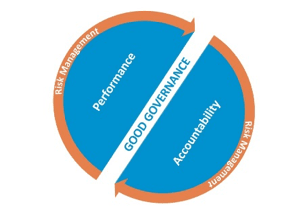

One way of describing the governance management arrangements that need to be put in place is via the paradigm outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Objectives of good governance. (Source: adapted from Australian National Audit Office, 2014, Public Sector Governance: Strengthening performance through good governance

Managing for accountability, or conformance, is generally better dealt with as there is considerable guidance and internal and external expertise available to put in place the governance arrangements to ensure conformance, as well as “public expectations of openness, transparency and integrity” (Australian National Audit Office, 2014, p7).

Public servants generally understand these concepts and agencies have procedures and guidance to achieve accountability although there are obviously exceptions.

Risk management is also well-understood and with risk management standards (such as ISO AS/NZS 31000) there is no need to spend time here discussing these in detail.

However, managing for performance is in our experience one of the least understood, particularly for public sector policy and program interventions. An agency may understand the concept of KPIs, collect data (metrics) and have some level of performance agreement with staff and providers. Though generally performance management is underdone or barely implemented.

The introduction of the enhanced framework of performance management under Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) has recognised the need for improving performance management in the public sector.

Managing for performance

As with the private sector, public sector programs need to align with the strategic agenda of the organisation, in this case the policy objectives of the government. Managing performance needs to demonstrate how well the program delivers against the policy objectives with ongoing monitoring, feedback and continuous improvement to ensure better alignment.

At this stage many bureaucrats may be rolling their eyes. How do you measure performance of a program against policy objectives when they are often vague, change is difficult (thus why there is a policy intervention), outcomes are long-term, may be dependent on many other factors, are intangible and have many variables?

The answer is that it is possible though it may not be easy. However, it can only be done with:

- a clear understanding of the objectives and program

- a well thought-through monitoring and reporting regime, including KPIs

- well-timed evaluations of the program

- ongoing collection of feedback tied into a continuous improvement approach

Define the objectives

Typically, policy objectives are defined very early on in the process and ‘set’ in such things as a new policy proposal.

These objectives are often very high-level or strategic and, more often than not, ambiguous. They may even be unable to be achieved within the period for which a program is funded, often only for an initial three to four years.

This can be problematic in terms of clarity on what is and isn’t expected of a program. It is therefore essential for managing performance that realistic, time bound expectations should be set against the outcomes and objectives.

There are various program evaluation techniques that can be used to help more clearly define the program including hierarchies. Basically the objective is to identify the outcomes which could realistically be expected within the program’s time frames. These are usually ‘short-term’ and ‘medium-term’ outcomes and not the long-term outcomes which are often the objectives of the policy/program.

It is difficult to generalise about how to define objectives. However, mapping of all program elements will be useful in most instances. The following can be used as a guide:

- Conduct an assessment of the role played by all stakeholders, including considering further consultation with those stakeholders.

- Identify the program inputs (for example, grant funds allocated, resources employed).

- Identify the expected outputs (for example, interviews conducted, training provided).

- Identify factors and variables that will affect outcomes, including constraints and other external influencing factors.

- Map the expected sequence of outcomes.

- Develop an understanding of the desired outcome path and undesired outcomes paths which may also signal potential points of measurement.

With this information it should be possible to start to define the program objectives which would meet the objectives or outcomes of the policy.

For example, a climate change program may have the policy objective of encouraging behavioural change and assisting industry to adapt. Clearly there are many things that would affect community behaviour and industry adaptation. But the program would need to clearly demonstrate some contribution to change. The only issue is then to define what level of contribution represents value for money on the taxpayer funds expended. This could still be defined relatively qualitatively.

Before finalising the design of the performance framework it may be appropriate to:

- develop a ‘baseline’ against which the impact of the program or intervention can be measured. This helps attribute the impact of the program as opposed to other external factors that may have positively or negatively affected results.

- consider if it may be appropriate to have separate implementation objectives as well as ongoing longer term objectives.

Monitor performance

Performance reporting is key to managing performance. There needs to be a comprehensive, well-targeted regime in place including use of KPIs. Performance reporting should not only address efficiency, administrative management and input/output measures but also seek to measure effectiveness against the program objectives.

Measuring effectiveness of the program can again be difficult. It would be typical that a mix of measures is required to obtain a balanced view of performance, including:

- input measures (for example, number of participants)

- output measures (for example, results achieved)

- trend measures (for example, percentage change) including assessing

- change against a baseline before the program commenced

- user/customer experience (for example, survey or focus groups)

Data sources will be a key consideration in finalising any KPIs whether it be from information collected as part of delivering the program (for example, forms completed by participants, reports from funding recipients), surveys or existing databases. The monitoring and reporting regime should focus on measuring trends against program objectives and other measurable aspects using data that can be readily collected.

A suitable report format will need to be developed that:

- covers the KPIs

- considers style (for example, traffic light)

- provides (brief) analysis or commentary of results, including any actions arising from them

Frequency of reporting will need to be considered, including whether all or some KPIs are calculated monthly, quarterly or annually. This is typically driven by the feasibility of collecting data on a more frequent basis. Some KPIs could be reported monthly and some annually.

The report format and content should also consider the intended audience which might include program management, the executive, Ministers and government and even the public.

Evaluate success of the program

A separate but related task is that the success of the program should be evaluated. This might include:

- following a pilot or, shortly after commencing, making necessary adjustments

- at a midpoint to capture lessons learned for improvements to better achieve the program objectives

- at the program’s conclusion to inform future policy-making or to obtain further funding

Evaluations typically cover a wider set of considerations and questions that are not generally part of a program’s day-to-day management and often not sufficiently addressed in the KPIs. For example, should the program continue to be funded? Such considerations and questions generally require specific, dedicated qualitative and quantitative methods and analysis which is beyond the scope of day-to-day data collection and monitoring.

In addition to evaluating performance, efficiency and effectiveness against the program/policy objectives, evaluations might also consider:

- appropriateness including whether the funding should continue

- integration, typically with other government programs

- strategic policy alignment

- program management and implementation

Good evaluation practice would involve development of an evaluation, monitoring and reporting strategy at the commencement of the program. This would typically contain the definition of the program objectives, KPIs, reporting requirements and key evaluation criteria.

This enables the identification of data sources and collection regimes to be put in place so that the data is available when the evaluation is conducted.

Evaluation approaches should consider mixed methods including both to enable a richer evaluation as well as a more accurate and evidenced-based approach. Data collection might include:

- quantitative data

- surveys, focus groups and interviews

- document reviews

- desktop research

- literature reviews

- case studies

The program evaluation should be designed to complement the existing measures and to give adequate cover to the more intangible and difficult to measure aspects of the program, for example, stakeholder views and economic impact analysis.

Collect feedback and continuously improve

In addition to the monitoring and evaluation of the program, feedback might be sought via other avenues on an ongoing basis. This might be as simple as online and hotline feedback channels right through to steering committees, reference groups, focus groups, piloting, user experience surveys and wider consultation.

The challenges most agencies face is to capture the feedback from all sources such that lessons can be learned, the program improved and insights for future policy development gleaned. Typically feedback is captured in various people’s heads or in the occasional document. Continuous improvement is often ad hoc at best and more often completely reactive to issues as they arise.

Agencies need to implement more robust improvement systems and processes to capture, consolidate, consider and act on feedback to achieve better policy objectives. This might include knowledge systems, lessons learned registers and the like. More importantly, it should include setting aside resources and time to consider, design and implement the improvements.

Regular continuous improvement forums (for example, every six months) may be one means but, like all good project management, someone needs to be responsible and timelines agreed.

Conclusion

Performance management of public sector programs against intangible policy objectives can be difficult. However, this does not dissolve responsibility for managing the performance of government programs to ensure success.

Agencies and program managers need to set clear objectives for the program during its implementation and operation. Measures need to be in place for each objective and reported on regularly, ideally in the form of KPIs and performance reporting.

More thorough evaluations of the program should be considered shortly after commencing or following a pilot, at a midpoint and at the end of the program.

Evaluations aim to assess the value of a program and to make improvements to achieve better programs objectives and to inform future policy making.

Finally it is key that feedback mechanisms are in place, including the KPIs and evaluation activities, to ensure that specific improvements are able to be captured, consolidated, considered and acted upon. The private sector implemented systematic structures and processes for continuous improvement many years ago and public sector program managers need to follow suit.